Recently I listened to an episode of The War on Cars, podcast posted on 31 January 2023, surprised to hear Dr Ian Walker talking about his latest research paper Motonormativity: How social norms hide a major public health hazard. A search on the internet produced the paper and several articles commenting on this paper. The study by Dr Ian Walker, Professor Alan Tapp and Dr Adrian Davis, set out to understand why the British people accept danger from driving that would not be accepted in other parts of life. They warned “such is the cultural ubiquity of these assumptions, described by the researchers as ‘Motonormativity’, that politicians are less likely to try to tackle issues such as pollution from vehicles or poor driving”.

Walker noticed that people tend to have a giant blindspot when it comes to certain behaviours associated with driving. “One of the things you notice if you spend your career trying to get people to drive less is people don’t like driving less.” He commented “We said, well, let’s try and measure this. Let’s just demonstrate the extent to which the population as a whole will make excuses, will give special freedom to the context of driving.”

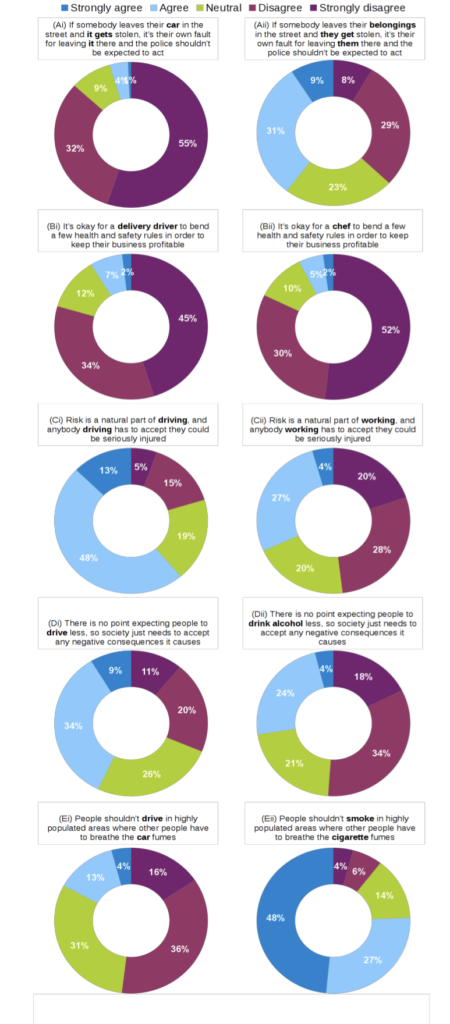

They surveyed 2157 members of the UK public. The participants were randomly assigned one of two sets of questions that sought their views on either driving related risk or a similar non-driving issue, having changed a couple of words, such as:

“People shouldn’t smoke in highly populated areas where other people have to breathe in the cigarette fumes,” changing two words to “People shouldn’t drive in highly populated areas where other people have to breathe in the car fumes”. The context was found to radically alter responses with 75% agreeing with ‘People shouldn’t smoke…’ but only 17% agreeing with ‘People shouldn’t drive…’.

Walker commented, “its nonsensical to say that making people breathe toxic air is a problem when it comes from a cigarette, but making people breathe toxic air is fine when it comes from a car. The underlying principle is the same, but people in our study were not using the same standards when they judged the two things.”

“It’s long been suspected that people can slip unconsciously into using different standards when they think about driving, leading them to commit a fallacy known as special pleading. Our study was intended to reveal this phenomenon and show just how substantial these effects can be,” said Walker.

The study indicates that people have an in-built acceptance of the risks and harm from motorists that they would not accept in other parts of life. This car blindness might create policies that increase air pollution and make travel more difficult and dangerous for all the people who move by other means.

“If you asked a politician whether a new hospital should be inaccessible to one-fifth of the population, obviously they’d say no” said Professor Alan Tapp “whereas if you asked the same politician whether a hospital should be built on the edge of town, it’s likely that many wouldn’t see the problem if they have a form of the mindset we’re looking at. But in practice, having the hospital outside town is not that different from making it inaccessible when a fifth of households don’t have a car”.

“We regularly see policy decisions – from the location of amenities to the design of streets – that overlook the needs of people who aren’t driving, often forcing them to make longer journeys or place themselves in danger for the convenience of people who are driving. We suggest that these shared assumptions demonstrated in our study, which we called ‘motonormativity’, are a big part of the reason that such problems don’t get noticed.”

“Every decision maker needs to get used to asking themselves, ‘What’s the underlying principle we’re considering here, and would I still be happy with it if we were talking about something other than road transport’” said Walker.

“If all you’ve ever known is a world where the needs of motorists come first, there’s a good chance you’re going to start to understand that is the ‘normal’ or even the ‘proper’ way of things,” said Dr Adrian Davis “when we pulled out just people who didn’t drive, we saw that even these people were using different standards when the questions asked about driving. Their answers tended to echo what the drivers were saying, meaning it’s not even simple self-interest at work. It’s got to be something deeper, rooted in our culture.”

Most people drive because it is a convenience. We tend to assume it’s part of the natural order to drive, which is why there’s so much hostility around cycling and alternate forms of transport: for many people it challenges the natural order of driving. “Not only do people do what the world makes easy, but because it feels easy, people conclude that it’s right,” Walker stated.

For Walker the smoking issue was particularly fascinating as society tolerated public smoking. But a growing awareness around public health risks associated with secondhand smoke led to a shift in the publics perception. He considered the same could be true for driving and where we could get to in the future, if people’s minds start to change. We don’t tend to view driving with public health concerns, which shields us from thinking about the societal harm and inequities associated with car use.

Having read the paper and the related media articles it is evident that motonormativity influences the majority of the population and we don’t have to look very far to be convinced of its existence: toucan crossings where pedestrians have to wait interminably after pressing the ‘beg button’, Derby Royal Hospital built on the edge of Derby (personal experience of having to catch two buses each way for hospital appointments when not feeling well), ‘road improvement schemes’ to aid the movement of vehicles, etc.

Everyday we make decisions that affect the health and welfare of our communities whether in our private lives, professional roles or as elected representatives: driving to the locals shops, buying a bigger car, supporting road improvement schemes, approving a new traffic scheme, etc. Car-ism continues to prioritise motor vehicle and to blight peoples lives, reducing and even eliminating transport choice. Councillors denigrate traffic calming schemes claiming they prevent plumbers and hairdressers getting to their customers.

We all make decisions that are influenced by our unconscious biases which have consequences on others, not intentionally but because we have not fully appreciated why we have made those choices. We must all question our decisions and question the decisions that those in positions of authority make on our behalf and to quote Walker ‘What’s the underlying principle we’re considering here, and would I still be happy with it if we were talking about something other than road transport’.